American Lung Association report finds air quality improvements, despite state-level resistance to regulation

The American Lung Association released its 17th State of the Air Report Wednesday. It found that overall national air quality is improving however many of the country’s largest and most polluted cities had their worst air quality years on record. The report findings, compiled from EPA-required public data, suggest that laws and policies like the Clean Air Act are responsible for the overall drop in pollution. Yet in recent months members of Congress, state lawmakers and electoral candidates have launched attacks on air quality protecting policies. FSRN’s Hannah Leigh Myers spoke with the ALA about their report and visited a one of a kind school in Denver for students that face life threatening illness if air quality protection regresses.

In most U.S. counties The National Weather Service issued fewer of these poor air quality alerts in 2015 than it had for the last few years. Paul Billings is National Senior Vice President of the American Lung Association and has monitored air quality for the organization for 25 years. He says overall he’s encouraged by this year’s data.

“The American Lung Association’s State of the Air report found continued improvement in air-quality from 2012 to 2014 in communities across the country especially with lower levels of year around particle pollution and ozone. But even with that continued improvement, we still see far too many people living in areas where the air is unhealthy to breathe,” explains Billings. “The report found that 52 percent of the people in the United States live in counties that have either unhealthful levels of ozone or particle pollution. More than 166 million Americans live in one of the 418 counties where they are exposed to unhealthy levels of air pollution.”

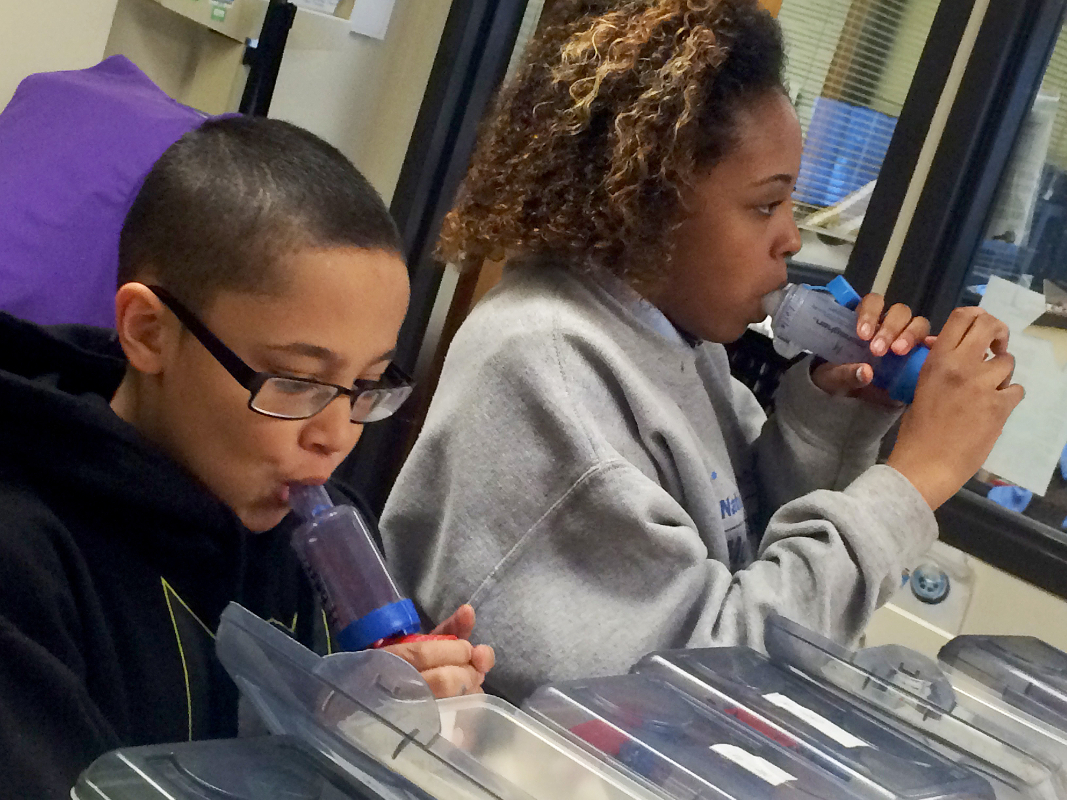

This year’s ALA report ranked Denver as a city with some of the worst air quality in the U.S. The city also happens to be home to the only school in the country where students meet with full time nurses multiple times a day for lung tests and treatments.

Founded in the 1970s, Morgridge Academy is a middle school at the National Jewish Health hospital for kids with respiratory illnesses, like severe asthma, that prevent them from attending regular schools.

Kathi Carney says unlike when she worked in the public school system, as a nurse at Morgridge Academy she can closely monitor the student’s serious respiratory illnesses, preventing asthma attacks before they happen and recognizing patterns in the student’s lung capacity.

“When the air quality is really poor, sometimes you can really tell,” Carney says. “Their numbers, we see them drop especially our kids with severe asthma, it affects them most definitely.”

Seventh grader Amadi has attended Morgridge since kindergarten, and for most of his life air quality has played a daily role in his safety and schedule, making him an air quality protection supporter.

“I do think it’s important. Our lives are at risk. In 20 years from now, if I’m still alive, I would want my life and my asthma to get better each day,” says Amadi. “If it’s getting worse each day then that’s just horrible. Nobody wants to spend their whole life in hospital.”

Amadi says that, like the overall data in State of the Air reports, he’s getting better. Lyndsay Moseley Alexander directs the ALA’s Healthy Air Campaign. She says politicians have a responsibility to keep kids like Amandi on a road to respiratory improvement by protecting and enforcing air quality laws.

“Implementation of the federal Clean Air Act is one of the highest priorities when it come to safeguarding the air that we breathe, because it is a chief public health law designed to reduce pollution and to protect our health,” Alexander explains. “In addition, it’s really important that we address climate change because climate change can make it harder to improve the air that we breathe. So we strongly support not only the Clean Air Act and implementation of that but also the Clean Power Plan which is a Clean Air Act rule to reduce carbon pollution and other pollutants.”

Research shows that since the Clean Air Act went into effect in the 1970s, air pollution has dropped by 70 percent while also allowing for economic growth. But in recent months, state and federal lawmakers have made several attempts to defund and scale back laws and agencies protecting air quality.

Just last week, the Colorado legislature debated a measure that could have defunded the state air-quality division. Ultimately, the cuts were not as deep as what bill sponsors sought. Colorado is also one of more than a dozen states suing the federal government over new pollution limits set in the Clean Power Plan. And multiple presidential candidates and lawmakers have pledged to defund the EPA, the agency that enforces air quality standards and provides a large portion of the data the ALA and other organizations use to monitor air quality.

The ALA’s Paul Billings says the fact that air quality protection has become a partisan political issue puts the future of every American’s health at risk.

“It’s interesting because clean air has always enjoyed broad bipartisan support,” Billings points out. “With the Clean Air Act in 1990 and then when it was last amended, in 1977 and 1970 when the act passed with overwhelming bipartisan support, unanimous support in some cases.”

A study by the American Association for the Advancement of Science found that although international policies to improve air quality appear to be dropping levels of pollution in most of the wealthiest countries, air pollution still caused more than 5.5 million premature deaths globally in 2015.

In the United States, the National Weather Service reports that air pollution-related illness costs the U.S. economy around $150 billion each year.