Ukrainian Security Service detained, tortured civilians in secret jails

In a recent report published by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch both organizations stated both sides in the eastern Ukraine conflict used torture and illegal detention. First published in July, the human rights groups described a secret prison located in the building of Ukraine’s security services in the city of Kharkov, in which 16 people were detained incommunicado.

The civilians, suspected of pro-Russian separatist activities, were held in secret captivity until a swap was arranged for Ukrainian prisoners of war held by pro-Russian separatist authorities. Ukraine’s security services have denied the existence of secret prisons while at the same time Ukraine’s general military prosecutor Anatoly Matios has promised to investigate the matter. Filip Warwick reports from Kiev.

Ukrainian’s Security Service, also known as the SBU, has been using its facilities to secretly detain civilians for periods ranging from 6 weeks to 15 months. That’s according to a recent report by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

“We can’t say what the overall number of victims is but we have very good grounds to believe that we are just scratching upon the surface, that the problem is much broader than the mere 18 cases that we documented,” says Tanya Lokshina, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch.

At the height of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine, government authorities and pro-Russian separatists abducted civilians to use as “human currency,” or bargaining chips to exchange for their captured fighters.

One such victim is 59-year-old dentist Kostyantyn Beskorovayni. He’s a former member of the Communist Party and a member of the local council of Kostyantynivka, a small town in eastern Ukraine.

He spent a total of 15 months in secret SBU detention sites. During that time, he was mistreated and forced into a false confession on camera – as dictated to him by his interrogators – of planning a terrorist attack.

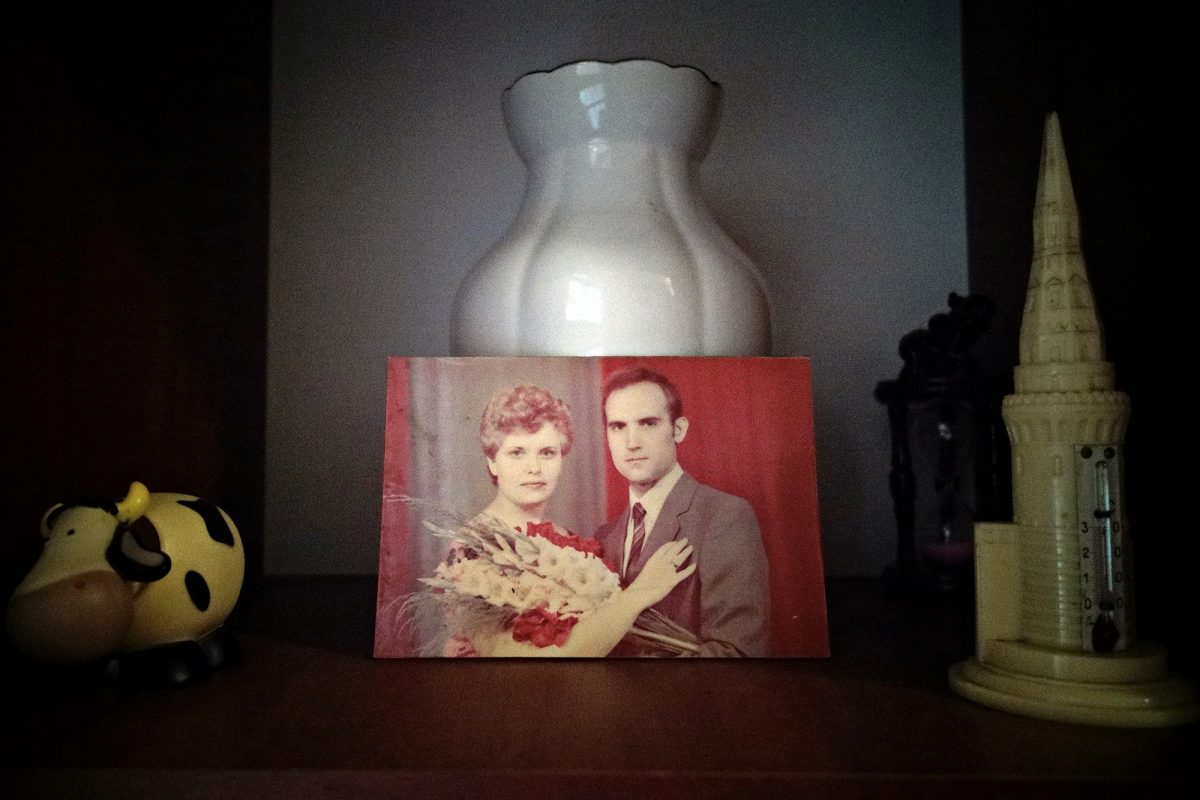

During Beskorovayni’s detention, his wife Olga, approached various Ukrainian authorities for information regarding his whereabouts. Her search for answers was fruitless.

She then went to Amnesty International, which put her in contact with a lawyer. The international scrutiny eventually led to her husband’s release, but Olga says the ordeal deeply affected him.

“What happens to a person that is detained – it’s difficult to talk about this. The people who abused my husband did a thorough job,” Olga Beskorovayni explains. “He’s not the same man that I knew before, he’s a changed person who’s been crushed and trampled upon.”

Beskorovayni says guards in the secret facility fueled despair among the inmates by calling them ghosts and telling them they no longer existed. To cope, he turned to religion.

“I began to read religious literature and we would pray during meal times. And so I would start every morning with a prayer, conclude the day with a prayer,” Kostyantyn Beskorovayni recalls. “I held the belief that with my faith I would return. I hoped – to get through this – and get back home. This was a spiritual test sent by God.”

Following the publication of the human rights report the SBU released an additional 12 men and a women from secret detention sites.

Among them was Mykola Vakaruk who, during his 600 days in secret detention, was taken to a Ukrainian hospital to treat his kidney failure. There, he was kept in an isolated room, handcuffed to the bed with two Ukrainian security agents guarding him at all times.

Krasimir Yankov, human rights researcher with Amnesty International, says secret detainees were kept invisible, even in hospitals.

“They were completely off the books, there were no records of them, they were not official prisoners, they didn’t have any papers,” Yankov points out. “So this person, Mykola Vakaruk, was actually registered under a fake name, if I’m not mistaken it was Ivanov Sergei Petrovich, and was in this hospital in Kharkiv for more than 30 days.”

Human rights groups believe at least five others are still being held incommunicado. Kostyantyn and Mykola hope that by coming forward with their stories they will motivate other victims to do the same and thereby make the so called “ghost detainees” visible.