Artists create ‘Visions from the Inside’ through letters from families in ICE detention

U.S. Immigration authorities have until October 23rd to release minors held in immigration detention facilities, according to a federal judge’s order. U.S. District Court Judge Dolly Gee of California ruled detaining minors in jail-like settings violates a long-standing, legally-binding agreement: the 1997 Flores Settlement. Immigration authorities argued the family detention policy serves as a deterrent. Legal experts say it’s likely hundreds will be in limbo as the case winds through the courts.

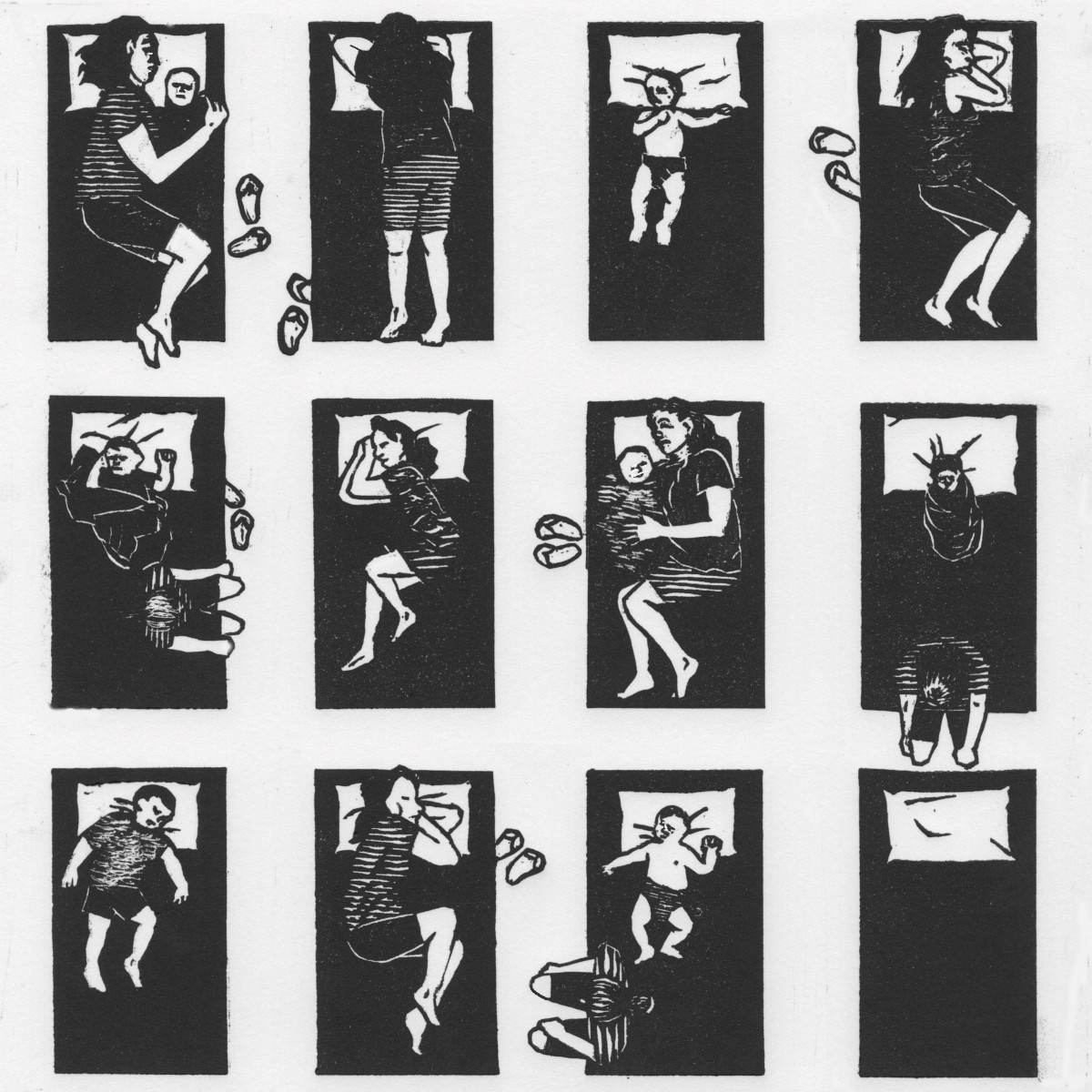

Life inside one of the facilities opened expressly to detain immigrant mothers with their children is the focus of a nation-wide art collaboration called Visions from the Inside. The collaborative was organized through CultureStrike, and was inspired by letters penned by detained women and children inside a family detention facility in Karnes County, Texas. Saadia Malik has more.

At his quiet East Oakland, California cottage, 35-year-old Robert Trujillo works as an artist and illustrator. He’s one of 15 artists selected by the San Francisco Bay Area based CultureStrike for Visions From the Inside, a collaboration in which illustrators visually interpret first-hand accounts, related in letters written by women and children held at a family detention center in South Texas.

Trujillo adapted one such letter, written by a 10-year-old named Miguel. The piece portrays details from the boy’s description of daily life in the detention center and includes a large man with an angry face on the front of his head, and a happy face on the back. The figure is hunched over and pointing at two children.

Trujillo says Miguel’s letter “talked about how the guards that they work with can be kinda two-faced and how some of them will be very kind when the media is around or when they feel like it, but when it comes to other things, they’ll just turn very quickly and be mean to them.”

Trujillo was invited to participate in the Visions from the Inside collaboration by CultureStrike’s Artist Project’s Manager Julio Salgado, a 31-year-old undocumented artist who also contributed a piece to the series. Salgado’s illustration shows a mother and son huddled inside an ice cube.

“It’s called hieleras – or iceboxes – because it gets really cold,” says Salgado, explaining that the mother who wrote the letter that inspired the piece said she’d been kept for seven days in a frigid detention cell. It’s a practice that immigrant detainees say is not uncommon. “A lot of the times they do this on purpose – immigration does this on purpose – so that people get desperate and then sign the self-deportation releases,” Salgado continues. “You sign the papers and that’s it, without seeing a judge or anything. And so the letter mentions – and I’m not gonna forget this – it mentions the mom mentioning how she celebrated her kid’s first birthday inside a detention center. And so I made this mom and this kid like hugging each other and there’s a birthday cake with the number one.”

Salgado says the concept behind Visions From the Inside stemmed from a conversation he had with a detainee during a visit to the Eloy Detention Center in Arizona earlier this year organized by Mariposas Sin Fronteras, an advocacy group for undocumented LGBTQ in detention.

“I noticed he was writing, he had pieces of paper,” recalls Salgado. ‘I asked him about the letter writings, ‘How important is it for you, letter writing?’ and he was just like ‘It’s the only way that I can tell my own story, it’s the only way that I can get in touch with organizations like Mariposas Sin Fronteras.’ People don’t write letters anymore. We live in a world of email and texting so you don’t realize how something so basic to a lot of us, to write a letter, how crucial it is to people in detention centers to communicate with the outside world.”

The letters that inspired Visions from the Inside are part of a digital archive provided by the End Family Detention network.

Detention capacity for holding mothers with children has expanded exponentially since the summer of 2014, during a spike in apprehensions of unaccompanied minors and of women with children along the border with Mexico. Most of those now in family detention are from Central America and are awaiting the outcomes of asylum claims.

The detention center in Karnes County, Texas is one of two large, for-profit facilities in South Texas opened since 2014 specifically to detain immigrant women with children.

“The government basically made the argument that we need to be able to use these fast-track deportation procedures to deport women and children and we really question whether that’s actually true,” says Stephen Kang, Equal Justice Rights Fellow with the American Civil Liberties Union Immigrants’ Rights Project. He insists the government has viable alternatives to detention. “It can instead just refer these women and children, most of whom have quite valid and strong asylum claims, and just refer them to regular removal proceedings before an immigration judge where they’re gonna get a full and fair chance to present their claim. And that would also not require them to be detained at these facilities, where these women and children are clearly suffering.”

A federal judge in California recently ruled that the detention of immigrant children in jail-like facilities is unlawful and in violation of a long-standing agreement known as the Flores Settlement, and has given the Obama administration until October 23rd to release the minors.

What will come after detention – or whether the mothers will be released with their children – remains to be seen.

Through their work, the artists behind Visions from the Inside hope to provide a glimpse of how women and children experience living in a prison-like setting in a way that people on the outside can understand.

[sdonations]2[/sdonations]