Napa High School’s choir reflects why investment in arts curriculum vital

California has one of the strongest policies on arts education in the country. But despite a state law that requires public schools provide access to arts education, many aren’t doing so, saying the funds simply aren’t available, particularly in disadvantaged communities.

The California legislature’s Joint Committee on the Arts recently met to examine the status of arts education in state schools. According to the Los Angeles Unified School District’s “Arts Equity Index,” only 35 out of the 639 district schools received an “A” for arts education. State and local leaders hope that as the economy improves, so will investment in school arts programs. But the reality, says Director of Arts Education Partnership Sandra Ruppert, is that the decision to fund arts programs comes down to the individual district, and in some cases the individual school. FSRN’s Karin Argoud visits the Napa High School campus in Napa California to visit to see just how true this is.

[sdonations]9[/sdonations]

Walking through the halls of Napa High School, a public high school in downtown Napa with a student body of 1900.

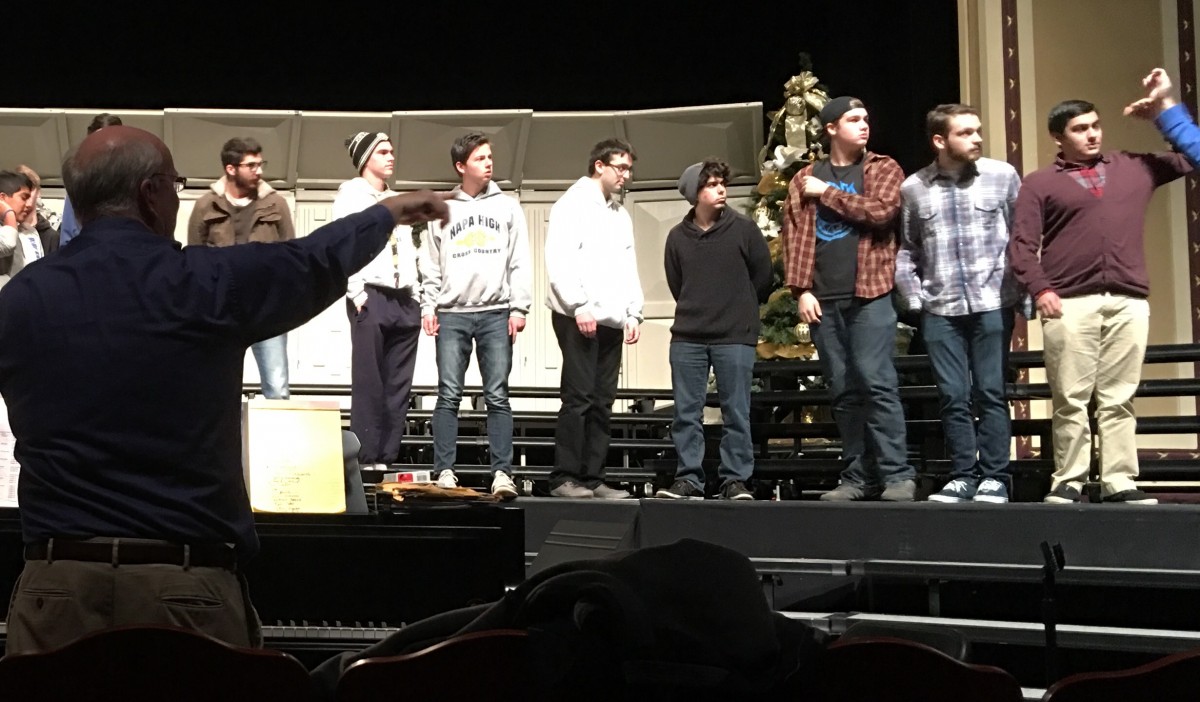

It’s easy to find the boys chorus class, you just listen.

The freshman boy energy is tangible in Voice 101, taught by teacher Travis Rogers. With more than 35 years teaching at Napa High, Rogers knows just how to harness their teenage testosterone while encouraging and empowering these young men to sing, for most of them for the first time in their lives. As class begins, he sets the tone during warm up and doesn’t waste a minute establishing order:

That’s when Rogers calls on one of the boys to come out in front and “police” his fellow singers, making sure their hands are down at their sides, they’re focused on Rogers’s directions, and that they’re engaging the audience both visually and vocally as they perform. And what happens if they catch a student breaking the rules? Ten pushups.

Rogers has a twinkle in his eyes as he says, “The pushups are a gentle way of making sure hey we’re all doing the right thing.”

The Napa Valley Unified School District funds his salary and provides the choir room for the program, and they even received $3,000 from the school site budget this year which was a first, says Rogers. But it’s surprising what it costs to run a chorus program. He says sheet music for one costs $20 thousand, and Napa is not a wealthy district. But most of the funding comes from private donations, concert ticket sales and donations made at performance gigs.

Marci Atkinson is Development Director at Napa’s nonprofit ALDEA. She says that even though the median income is high in Napa County, there is significant income disparity, “meaning there are a good proportion of people that are very poor and then there are people that are very wealthy at the very top the kind of skew the medium income.”

The district is comprised of more than 30 schools serving about 18,000 students. More than half are Hispanic and 44 percent qualify for free and reduced meals. According to a study by the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health, 43 percent of Napa County children live in households that earn less than the Self-Sufficiency Standard, meaning their families don’t earn enough to afford basic housing, food, childcare, transportation and healthcare costs.

Annie Peetrie, the principal at Napa High, says the chorus program is open to all interested students, irrespective of their singing ability.

“What comes to mind is walking a student down to Travis, maybe a new student enrolled from another school, maybe it’s a ninth grader who has yet to find success in school or hasn’t connected, and walking that student down to see choir so that they open their mind to take it on, and watching Travis interact with the student and really take any kid. And that sticks in my mind,” explains Peetrie. “What fuels him the most is taking the kid that has never sang before.”

Like 14 year-old Chase La Rue, a freshman football player and wrestler. It’s obvious that La Rue is an athlete: he’s small, but muscular and lean, with a bleach blond crew cut.

“First it was kind of nerve wracking, I mean just singing in front of faces that I don’t know and haven’t met yet,” La Rue recalls. “But then, once we start going, we became a family and can really sing to each other and stuff like that. It’s just a fun time. And most of the football team does it, so? I can’t explain it. More like kinda, like calm down. it’s just a nice calm thing. Just relax and have fun.”

Jayro Garcia, a tall, lanky junior who has been in choir since he was a freshman, elaborates: “Say you’re having a bad day or something, like you don’t really want to talk to anybody but in choir you’re kind of force to sing. But, once you start getting into those songs and start getting into the lyrics, it kind of just, everything else just floats away because you’re focusing on one thing, and it’s a joyful thing.”

Rogers says that they go after the athletes. Typically, more than 80 percent of his singers are athletes.

Peetrie adds that much like athletics, Mr. Travis creates a team atmosphere in the classroom.

“He has high expectations for kids, which is what we want in every classroom,” explains Peetrie. “But he does that in a way where they are a part of a team and it’s the same reason why kids go back and play sports after working really hard, grueling workouts, they do it because they are a part of something and that’s what Travis creates.”

According to a study by the National Endowment for the Arts, arts education bolsters student achievement and contributes to stronger participation in school activities. Napa High has the largest enrollment of male singers at a public high school in the United States: Of the 350 students, 190 are boys.

And it’s not only the athletes the choir attracts, or the artsy kids on the fringes that the choir attracts, adds Rogers. The program brings all types of student together, students who likely wouldn’t otherwise interact.

“Perhaps the strongest thing, though, is the community that it builds. The fact that everybody is accepted, and then that any type of kid can walk in that door, and they have a place they can do well and be accepted,” Rogers says. “And that’s been the great joy in teaching these kids that they can sing, it’s okay to sing, that it’s cool to sing, but more importantly that they find a place where they’re safe and where they’re valued. It’s been the magic here.”

Junior Jayro Garcia says there’s a level playing field in the choir room. “We treat each other as equals,” points out Garcia. “So, all that, maybe racism and otherwise criticism, just kind of floats away and we all get along together.”

“We teach a functioning society in that room. We’re in need of that with our kids,” says Rogers. “Music should be required just as much as English and as math is, because in the hands of good professionals, you can create something that’s just exceedingly special.”